Before the Chinese Communist invasion of 1950 Tibet was a fully functioning and independent state. It threatened none of its neighbors, fed its population unfailingly, year after year, with no help from the outside world. Tibet owed no money to any country or international institutions, and maintained basic law and order. Tibet banned capital punishment in 1913 (mentioned by a number of foreign travelers1) and was one of the first countries in the world to do so. There is no record of it persecuting minorities (e.g. Muslims2) or massacring sections of its population from time to time as China and some other countries do – remember Tiananmen. Although its frontiers with India, Nepal and Bhutan were completely unguarded, virtually no Tibetan fled their country as economic or political refugees. There was not a single Tibetan immigrant in the USA or Europe before the Communist invasion.

Before the Chinese Communist invasion of 1950 Tibet was a fully functioning and independent state. It threatened none of its neighbors, fed its population unfailingly, year after year, with no help from the outside world. Tibet owed no money to any country or international institutions, and maintained basic law and order. Tibet banned capital punishment in 1913 (mentioned by a number of foreign travelers1) and was one of the first countries in the world to do so. There is no record of it persecuting minorities (e.g. Muslims2) or massacring sections of its population from time to time as China and some other countries do – remember Tiananmen. Although its frontiers with India, Nepal and Bhutan were completely unguarded, virtually no Tibetan fled their country as economic or political refugees. There was not a single Tibetan immigrant in the USA or Europe before the Communist invasion.

Independent Tibet

This blog is about Tibet Facts, the basic information of Tibet.

Tibet a Functioning State

Before the Chinese Communist invasion of 1950 Tibet was a fully functioning and independent state. It threatened none of its neighbors, fed its population unfailingly, year after year, with no help from the outside world. Tibet owed no money to any country or international institutions, and maintained basic law and order. Tibet banned capital punishment in 1913 (mentioned by a number of foreign travelers1) and was one of the first countries in the world to do so. There is no record of it persecuting minorities (e.g. Muslims2) or massacring sections of its population from time to time as China and some other countries do – remember Tiananmen. Although its frontiers with India, Nepal and Bhutan were completely unguarded, virtually no Tibetan fled their country as economic or political refugees. There was not a single Tibetan immigrant in the USA or Europe before the Communist invasion.

Before the Chinese Communist invasion of 1950 Tibet was a fully functioning and independent state. It threatened none of its neighbors, fed its population unfailingly, year after year, with no help from the outside world. Tibet owed no money to any country or international institutions, and maintained basic law and order. Tibet banned capital punishment in 1913 (mentioned by a number of foreign travelers1) and was one of the first countries in the world to do so. There is no record of it persecuting minorities (e.g. Muslims2) or massacring sections of its population from time to time as China and some other countries do – remember Tiananmen. Although its frontiers with India, Nepal and Bhutan were completely unguarded, virtually no Tibetan fled their country as economic or political refugees. There was not a single Tibetan immigrant in the USA or Europe before the Communist invasion.

Foreign Military Invasion not “Peaceful Liberation”

On the dawn of 6th October 1950, the 52nd, 53rd & 54th divisions of the 18th Army3 of the Red Army (probably over 40,000 troops) attacked the Tibetan frontier guarded by 3,500 regular soldiers and 2,000 Khampa militiamen. Recent research by a Chinese scholar reveals that Mao Zedong met Stalin on 22nd January 1950 and asked for the Soviet air force to transport supplies for the invasion of Tibet. Stalin replied: “It’s good you are preparing to attack Tibet. The Tibetans need to be subdued.

On the dawn of 6th October 1950, the 52nd, 53rd & 54th divisions of the 18th Army3 of the Red Army (probably over 40,000 troops) attacked the Tibetan frontier guarded by 3,500 regular soldiers and 2,000 Khampa militiamen. Recent research by a Chinese scholar reveals that Mao Zedong met Stalin on 22nd January 1950 and asked for the Soviet air force to transport supplies for the invasion of Tibet. Stalin replied: “It’s good you are preparing to attack Tibet. The Tibetans need to be subdued.An English radio operator (employed by the Tibetan government) at the Chamdo front wrote that Tibetan forward defences at the main ferry point on the Drichu River fought almost to the last man.5 In the south at the river crossing near Markham, the Tibetan advance guards fought heroically but were wiped out, according to an English missionary there.6 Surviving units conducted fighting retreats westwards, in good order. No unit fled or surrendered. Four days into the retreat, one regiment was overwhelmed and destroyed. Only two weeks after the initial attack, the Tibetan army surrendered. The biography of a Communist official states “Many Tibetans were killed and wounded in the Chamdo campaign.”7 and “… the Tibetan soldiers fought bravely, but they were no match for the superior numbers and better training” of the Chinese forces. According to the only Western military expert who wrote on the Chinese invasion of Tibet “…the Reds suffered at least 10,000 casualties.”8

It was not a peaceful liberation of Tibet as Beijing claims. In 1956 the Great Khampa revolt started and spread throughout the country culminating in the March Uprising of 1959. Guerilla operations only ceased in 1974. “A conservative estimate would have to be no less than half-a-million”9 Tibetans killed in the fighting. Many more died in the subsequent political campaigns, forced labor camps (laogai) and the great famine. The revolutionary uprisings throughout Tibet in 2008 and the brutal Chinese crackdown clearly demonstrate that the struggle continues today.

National Flag of Tibet

The modern Tibetan national flag was adopted in 1916.10 Its first appearance before the world was in National Geographic Magazine’s “Flags of the World” issue of 1934 11 and other publications, and was reproduced in the early thirties in cigarette card collections in Europe.12 The flag was probably too new and unknown to appear in the very first flag issue (1917) of the National Geographic, but Tibet did receive mention in an article on medieval flags in that same issue.13 According to an eminent vexillologist, Professor Lux-Worm, the national flag of Tibet was based on an older 7th century snow lion standard of the Tibetan Emperor, Songtsen Gampo.14 It should be borne in mind that over 90% of the flags of the nations in the UNO were created after WWII, including the present national flag of China.

The modern Tibetan national flag was adopted in 1916.10 Its first appearance before the world was in National Geographic Magazine’s “Flags of the World” issue of 1934 11 and other publications, and was reproduced in the early thirties in cigarette card collections in Europe.12 The flag was probably too new and unknown to appear in the very first flag issue (1917) of the National Geographic, but Tibet did receive mention in an article on medieval flags in that same issue.13 According to an eminent vexillologist, Professor Lux-Worm, the national flag of Tibet was based on an older 7th century snow lion standard of the Tibetan Emperor, Songtsen Gampo.14 It should be borne in mind that over 90% of the flags of the nations in the UNO were created after WWII, including the present national flag of China.

National Anthem

Maps of Tibet

Many pre-1950 maps, globes and atlases showed Tibet as an independent nation separate from China. Some of the earliest maps on record of Asia show Tibet (variably spelled as Tobbat, Thibbet, or the Kingdom of Barantola) as separate from China or Cathay. A map of Asia drawn by the Dutch cartographer, Pietar van der Aa around 1680 shows Tibet in two parts but distinct from China;[18] as does a 1700 map drawn by the French cartographer Guillaume de L’isle, where Tibet is referred to as the “Kingdom of Grand Tibet.” [19] A map of India, China and Tibet published in the USA in 1877 represents Tibet as distinct from the two other nations.[20] An 1827 map of Asia drawn by Anthony Finley of Philadelphia, clearly shows “Great Thibet” as distinct from the Chinese Empire.[21]

Many pre-1950 maps, globes and atlases showed Tibet as an independent nation separate from China. Some of the earliest maps on record of Asia show Tibet (variably spelled as Tobbat, Thibbet, or the Kingdom of Barantola) as separate from China or Cathay. A map of Asia drawn by the Dutch cartographer, Pietar van der Aa around 1680 shows Tibet in two parts but distinct from China;[18] as does a 1700 map drawn by the French cartographer Guillaume de L’isle, where Tibet is referred to as the “Kingdom of Grand Tibet.” [19] A map of India, China and Tibet published in the USA in 1877 represents Tibet as distinct from the two other nations.[20] An 1827 map of Asia drawn by Anthony Finley of Philadelphia, clearly shows “Great Thibet” as distinct from the Chinese Empire.[21] Probably the largest stained glass globe in the world (in Boston), based on the Rand McNally 1934 map of the world, clearly shows Tibet as a separate nation.[22] (Tibet is in pink above India) Following the publication of the great atlas commissioned by the Manchu Emperor Kangxi and created by Jesuit cartographers, some European maps in the mid-1700s began to depict Tibet as part of China. The Jesuits could not personally survey Tibet (as they had surveyed China and Manchuria) since Tibet was not part of the Chinese Empire. So they trained two Mongol monks in Beijing and sent them to make a secret survey of Tibet. Similar clandestine surveys of Tibet were conducted by British mapmakers using trained Himalayan natives and even a Mongol monk. An American sinologist has observed that, like European colonial powers, China could be said to have used cartography to further its “Colonial Enterprise” in Tibet and Korea.[23]

Following the publication of the great atlas commissioned by the Manchu Emperor Kangxi and created by Jesuit cartographers, some European maps in the mid-1700s began to depict Tibet as part of China. The Jesuits could not personally survey Tibet (as they had surveyed China and Manchuria) since Tibet was not part of the Chinese Empire. So they trained two Mongol monks in Beijing and sent them to make a secret survey of Tibet. Similar clandestine surveys of Tibet were conducted by British mapmakers using trained Himalayan natives and even a Mongol monk. An American sinologist has observed that, like European colonial powers, China could be said to have used cartography to further its “Colonial Enterprise” in Tibet and Korea.[23]

Tibetan Currency

Even after the Communist invasion, Tibetans successfully undermined Chinese efforts to take over its currency. Official Chinese currency only came into use after the departure of the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan government from Tibet in March 1959.26

Even after the Communist invasion, Tibetans successfully undermined Chinese efforts to take over its currency. Official Chinese currency only came into use after the departure of the Dalai Lama and the Tibetan government from Tibet in March 1959.26

Tibetan Passports

The Tibetan government gave its approval for the first-ever Everest expedition (1921). Charles Bell, the visiting British diplomat in Lhasa wrote “I received from the Tibetan Government a passport in official form, which granted permission for the climbing of Mount Everest.”[28] The subsequent Everest expeditions of 1922, 1924 and 1936[29] also received passports from the Tibetan government. Passports were sometimes issued for scientific undertakings: the Schaeffer expedition of 1939,[30] Tucci’s expedition of 1949 [31] and the plant hunter Frank Kingdon Ward in 1924.[32]

The Tibetan government gave its approval for the first-ever Everest expedition (1921). Charles Bell, the visiting British diplomat in Lhasa wrote “I received from the Tibetan Government a passport in official form, which granted permission for the climbing of Mount Everest.”[28] The subsequent Everest expeditions of 1922, 1924 and 1936[29] also received passports from the Tibetan government. Passports were sometimes issued for scientific undertakings: the Schaeffer expedition of 1939,[30] Tucci’s expedition of 1949 [31] and the plant hunter Frank Kingdon Ward in 1924.[32] President Roosevelt’s two envoys to Tibet in 1942 were presented their passports at Yatung.[33] The Americans Lowell Thomas Jr. and Sr. visited Tibet in 1949, and were issued “Tibetan passports” at Dhomo. “When the Dalai Lama’s passport was spread out before us, I could not help thinking that many Western explorers who had failed to reach Lhasa would have highly prized a document like this.” [34]

The first modern Tibetan passport [35] with personal information, photograph and space for visas and endorsements was issued in 1948 to members of the Tibetan trade mission. It was modeled on the international one-page fold-out model of 1915. Britain, USA and seven other countries issued visas and transit visas for this document.

Treaties

As an independent nation, Tibet entered into treaties with neighboring states: Bushair 1681, Ladakh 1683 and 1842, Nepal 1856 and so on.

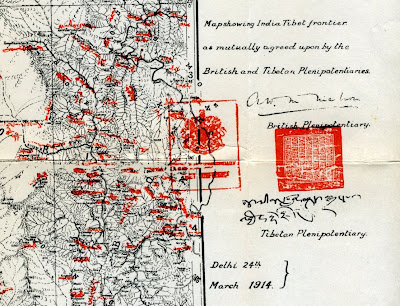

Tibet signed a number of treaties and conventions with Britain culminating in the Simla Treaty of 1914 by which British India and Tibet reached an agreement on their common frontier.[37] India’s present-day claims to the demarcation of its northern border is based on this treaty which was signed by Tibet – not China.

In January 1913, Tibet and Mongolia signed a treaty in Urga, the preamble of which reads: “Whereas Mongolia and Tibet having freed themselves from the Manchu dynasty and separated themselves from China, have become independent states, and whereas the two States have always professed one and the same religion, and to the end that their ancient mutual friendships may be strengthened…”[38] Declarations of friendship, mutual aid, Buddhist fraternity, and mutual trade etc. follow in the various articles. The Tibetan word “rangzen” is used throughout to mean “independence”.

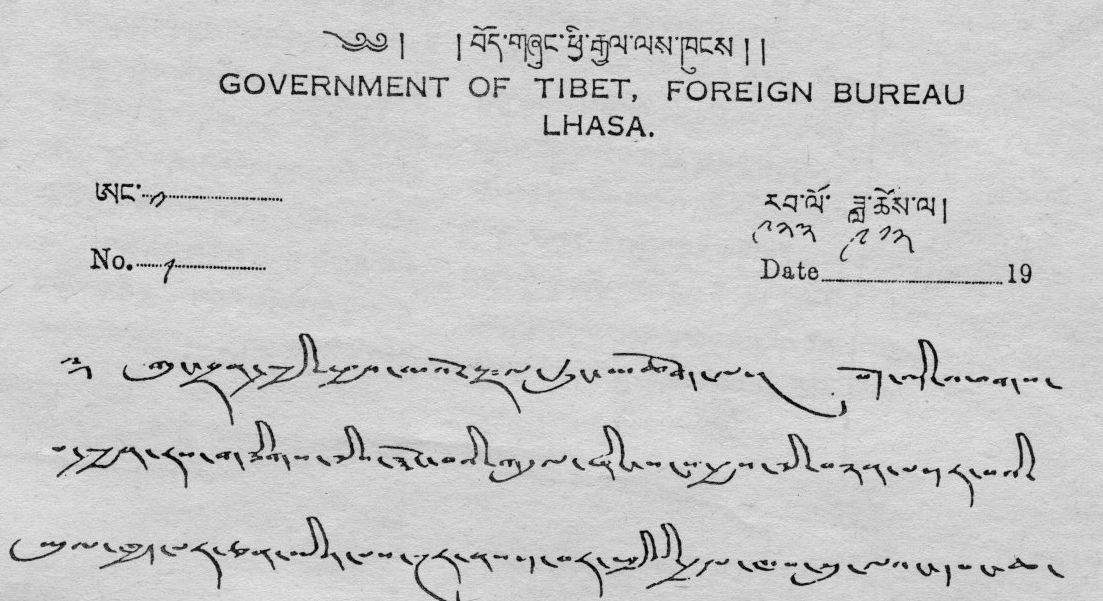

A Tibetan Bureau of Foreign Affairs was established in 1942, which conducted diplomatic relations (and correspondence[39]) with Britain, USA, Nepal, independent India and China.

Post & Telegraph System

A telegraph line from India to Lhasa was completed in 1923, along with a basic telephone service.44 Both were open for public use. The Tibetan capital was electrified in 1927. The work of installing both the hydroelectric plant and the distribution system was undertaken near “single-handedly”45 by a young Tibetan engineer, Ringang. All these projects were initiated and paid for by the Tibetan government. Radio Lhasa was launched in 1948 and broadcasted news in Tibetan, English and Chinese.46

A telegraph line from India to Lhasa was completed in 1923, along with a basic telephone service.44 Both were open for public use. The Tibetan capital was electrified in 1927. The work of installing both the hydroelectric plant and the distribution system was undertaken near “single-handedly”45 by a young Tibetan engineer, Ringang. All these projects were initiated and paid for by the Tibetan government. Radio Lhasa was launched in 1948 and broadcasted news in Tibetan, English and Chinese.46

Witnesses To Independent Tibet

It is almost certain that none of the official propagandists who demonize Tibet in Chinese publications had witnessed life in old Tibet. In fact, none of Beijing’s Tibet propagandists in the West (Michael Parenti, Tom Grunfeld, Barry Sautman et al)[53] had visited Tibet before 1980. They often misrepresent the old Tibetan society and government with select quotes from English journalists and officials (L. A. Waddell, Percival Landon, Edmund Candler, Captain W.F.T. O’Connor) who accompanied the British invasion force of 1904, and who sought to justify that violent imperialist venture into Tibet by demonizing Tibetan society and institutions.

The only high-ranking Chinese official with scholarly credentials who spent any length of time in old Tibet was Dr. Shen Tsung-lien, representative of the Republic of China in Lhasa (1944-1949). In his book Tibet and the Tibetans, Dr. Shen writes of a nation clearly distinct from China, and one that “…had enjoyed full independence since 1911.” He writes truthfully of a hierarchical, conservative society “fossilized many centuries back” but whose people were orderly, peaceable and hospitable – but also “notorious litigants,” adding that “few peoples in the world are such eloquent pleaders.” Shen also mentions “Appeals may be addressed to any office to which the disputants belong, or even to the Dalai Lama or his regent.”[54]

The only high-ranking Chinese official with scholarly credentials who spent any length of time in old Tibet was Dr. Shen Tsung-lien, representative of the Republic of China in Lhasa (1944-1949). In his book Tibet and the Tibetans, Dr. Shen writes of a nation clearly distinct from China, and one that “…had enjoyed full independence since 1911.” He writes truthfully of a hierarchical, conservative society “fossilized many centuries back” but whose people were orderly, peaceable and hospitable – but also “notorious litigants,” adding that “few peoples in the world are such eloquent pleaders.” Shen also mentions “Appeals may be addressed to any office to which the disputants belong, or even to the Dalai Lama or his regent.”[54]

Reference Notes

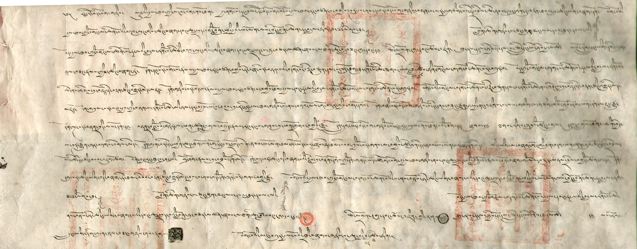

See index:

“Capital punishment abolished in Tibet, 142, 143, 236.”

Byron, Robert. First Russia then Tibet. London: Macmillan & Co., 1933. pg 204: “Capital punishment was now abolished.”

McGovern, William. To Lhasa in Disguise. New York: Century Co., 1924. pg 388-389.

Kingdon-Ward, Frank. In the Land of The Blue Poppies. New York: Modern Library, 2003. pg 22.

Winnington, Alan. Tibet: The Record of a Journey. London: Lawrence & Wishart Ltd., 1957.

2 Henry, Gray. Islam in Tibet. Louisville, Kentucky: Fons Vitae, 1997.

Nadwi, Dr. Abu Bakr Amir-uddin. Tibet and Tibetan Muslims, Dharamsala: Library of Tibetan

Works & Archives, 2004.

3 Goldstein, Melvyn. A Tibetan Revolutionary: The Political Life and Times of Bapa Phuntso

Wangye. University of California Press, 2004, pg 137

4 Chang, Jung & Jon Halliday. Mao: The Unknown Story. London: Jonathan Cape, 2005.

5 Ford, Robert. Captured in Tibet. London: George G. Harrap & Co., Ltd, 1957. pg 158.

6 Bull, Geoffrey T. When Iron Gates Yield. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1955. pg 130.

7 Goldstein, Melvyn. A Tibetan Revolutionary: The Political Life and Times of Bapa Phuntso

Wangye. University of California Press, 2004, pg 139.

8 O’Ballance, Edgar. The Red Army of China. London: Faber & Faber, 1962. pg 189-190.

9 Norbu, Jamyang. “The Forgotten Anniversary – Remembering the Great Khampa Uprising of

1956″. Thursday, December 07, 2006, Phayul. https://www.phayul.com/news/article.aspx?id=14993&t=1&c=4

10 Tsarong, Dundul Namgyal. In the Service of His Country: The Biography of Dasang Damdul

Tsarong Commander General of Tibet. Ithaca: Snow Lion Publications, 2000. pg 51

11 Grosvenor, Gilbert and William J. Showalter, “Flags of the World”. The National Geographic

Magazine: September, 1934 - Vol. LXVI - No. 3. Washington, D.C.” National Geographic

Society, 1934.

12 Tibet Nationalflagge, Bulgaria Zigarettenfabrik, Dresden,1933. (From a series non-European countries, pictures 201-400) Courtesy of Prof. Dr. Jan Andersson.

13 Grosvenor, Gilbert H. “The Heroic Flags of the Middle Ages.” The National Geographic

Magazine: October, 1917 - Vol. Xxxii - No. 4. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic

Society, 1917.

14 Lux-Wurm, Pierre C. “The Story of the Flag of Tibet.” Flag Bulletin: Vol. XII - No. 1. Spring

1973.

15 OLD TIBETAN NATIONAL HYMN

Ghang ri rawe kor we shingkham di

Phen thang dewa ma loe jungwae ne

Chenrezig wa Tenzin Gyatso yin

Shelpal se thae bhardu

Ten gyur chik

Circled by ramparts of snow-mountains, This sacred realm, This wellspring of all benefits and happiness Tenzin Gyatso, bodhisattva of Compassion. May his reign endure Till the end of all existence

(my translation)

The eminent Tibetan scholar, Tashi Tsering citing the historical work Bka’ blon rtogs brjod, says that this verse was composed by the Tibetan ruler, Phola lha nas, (in 1745/46) in praise of the 7th Dalai Lama. “Reflections on Thang stong rgyal po as the founder of the a lce lha mo tradition of Tibetan performing arts,”The Singing Mask: Echoes of Tibetan Opera, Lungta Winter 2001 No 15, eds. Isabelle Henrion-Dourcy and Tashi Tsering)

16 Audio clip of namthar (opera aria) of National Hymn sung by Techung. Courtesy of Chaksampa

17. TIBETAN NATIONAL ANTHEM

Sishe phende dhoe gu jung wei ter

Thubten sampel norbu honang bar

Tendro nor dzin gyache kyong wey gon

Trinle kyi rolsto gye

Dorje kham sum tenpey

Chok kun jham tse kyong

Nam khoe gawa gyaden u pang gungla beg

Phuntso deshi nga thang gye

Bhojong cholkha sum gyi kyonla deyden sar pey khyap

Chosi kyi pelon tar

Thubten chochu gyepe dzamling yangpi kyegu shidi pela jor

Bhojong tendro getzen nyi woe kyi

Tashi woe nang humdu tro mi zi

Nachoe munpey yul ley gye gyur chi

TIBETAN NATIONAL ANTHEM (Translation)

The source of temporal and spiritual wealth of joy and boundless benefits

The Wish-fulfilling Jewel of the Buddha’s Teaching, blazes forth radiant light

The all-protecting Patron of the Doctrine and of all sentient beings

By his actions stretches forth his influence like an ocean

By his eternal Vajra-nature

His compassion and loving care extend to beings everywhere

May the divinely appointed rule achieve the heights of glory

And increase its fourfold influence and prosperity

May a golden age of joy and happiness spread once more through the three regions of Tibet

And may its temporal and spiritual splendour shine again

May the Buddha’s Teaching spread in all the ten directions and lead all beings

in the universe to glorious peace

May the spiritual Sun of the Tibetan faith and People

Emitting countless rays of auspicious light

Victoriously dispel the strife of darkness

Lyrics composed in 1959 by Kyapje Trichang Rinpoche, tutor of His Holiness the Dalai Lama.

18 Image. A map of Asia drawn by the Dutch cartographer, Pietar van der Aa around 1680 shows

Tibet in two parts but distinct from China.

19 Image. A map of Asia drawn by the French cartographer, Guillaume de L’isle, around 1700,

where Tibet is referred to as the “Kingdom of Grand Tibet.”

20 Image. “Map of Hindoostan, Farther India, China and Tibet”. Constructed & engraved by

W.Williams, Phila. Entered according to Act of Congress in the year 1877 by S Augustus

Mitchell in the Office of the Librarian of Congress at Washington.

21 Image. An 1827 map of Asia drawn by Anthony Finley of Philadelphia, clearly showing “Great

Tibet” as distinct from the Chinese Empire.

22 The Mapparium, is a thirty-foot stained-glass globe room in the lobby of the Christian Science

Publishing Society in Boston, which gives one a unique “inside view” of the world. The

political boundries are frozen circa 1935. It was based on Rand McNally’s 1934 map

of the world,. At this size, the scale amounts to approximately 22 miles to the inch.

In the photograph Tibet (pink) can be seen directly at the back above British India (red)

and to the side of China (yellow).

Check URL for history and directions. http://www.roadsideamerica.com/story/11455

http://designorati.com/articles/t1/cartography/329/mary-baker-eddys-marvelous-mapparium.php

23 Hostetler, Laura. Qing Colonial Enterprise: Ethnography and Cartography in Early Modern

China. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001.

24 Bertsch, Wolfgang. The Currency of Tibet. Dharamsala: Library of Tibetan Works & Archives, 2002.

25 Bertsch, Wolfgang. A Study of Tibetan Paper Money: With a Critical Bibliography, Dharamsala: Library of Tibetan Works & Archives, 1997.

26 Rhodes, N.G. “The First Coins Struck in Tibet”. Tibet Journal. Winter 1990: (LTWA), Dharamsala.

27 Richardson, Hugh. “Reflections on a Tibetan Passport”. High Peaks Pure Earth: Collected

Writings on Tibetan History & Culture. London: Serindia Publications, 1998. pg 482.

28 Bell, Charles. Portrait of a Dalai Lama: The Life and Times of the Great Thirteenth. Boston:

Wisdom Publications, 1987. pg 278.

29 Gould, B.J. The Jewel in the Lotus: Recollections of an Indian Political. London: Chatto &

Windus, 1957. pg 210-211.

30 Englehardt, Isrun. Tibet in 1938-39: Photographs from the Ernst Schafer Expedition to Tibet. Chicago: Serindia, 2007. pg 121.

31 Tucci, Guiseppe. To Lhasa and Beyond. New Delhi: Oxford and IBH, 1983. pg 14-15.

32 Cox, Kennith. Frank Kingdon Ward’s, Riddle of the Tsangpo Gorges. United Kingdom: Antique Collector’s Club, 2001. pg 75.

33 Tolstoy, Lt.Col. Ilia. “Across Tibet From India To China”. The National Geographic Magazine. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic Society, August 1946. “This letter was a piece of red cotton cloth about 16 inches wide and two feet long, to be carried in the bosom or on a staff by an outrider who would precede the party by one or two days. It stated that two American officers were en route to visit the Dalai Lama…”

34 Thomas, Lowell Jr. Out of This World: Across the Himalayas to Forbidden Tibet. New York: The Greystone Press, 1950. pg 79-80.

35 Facsimile of Shakabpa passport

36 Photograph. Treaty Pillar of AD 821-822 within protective enclosure.

37 The Sino-Indian Boundary Question (Enlarged Edition). Peking: Foreign Language Press, 1962. Photostat of eastern sector of original map of the McMahon line with signatures and seals of Tibetan and British plenipotentiaries, Delhi 24 March 1914. Original scale 1:5000,000.

38 Facsimile of the Tibet-Mongolia Treaty of 1913, and English translation.

39 Facsimile of Tibetan Foreign Bureau letter (and English translation) to Mao Tse-tung in 1949 .

40 Waterfall, Arnold C. The Postal History of Tibet. London: Robson Lowe Ltd., 1965.

41 Images of Tibetan stamps and covers.

42 Chapman, F. Spencer. Lhasa the Holy City. London: Chatto and Windus, 1940. pg 87.

43 Cis, Peter. Tibet, Through the Red Box. New York: Francis Foster Books, 1998.

44 David, MacDonald. Twenty Years in Tibet. New Delhi: Vintage Books, 1991. (first published 1932). pg 287.

45 Tsarong, Dundul Namgyal. In the Service of His Country: The Biography of Dasang Damdul

Tsarong Commander General of Tibet. Ithaca: Snow Lion Publications, 2000. pg 62.

46 Brauen, Martin. Peter Aufschnaiter’s Eight Years in Tibet. Bangkok: Orchid Press, 2002.

In 1948, Radio Lhasa started the first of its daily broadcasts to the outside world. At five p.m., the station would go on air. The news was read in Tibetan, and then in English by Reginald Fox or by Kyibuk, one of the surviving Rugby students and an official at the Tibetan Foreign Bureau. Finally, the news was read in Chinese by Phuntsok Tashi Takla, the Dalai Lama’s brother-in-law. Official announcements were also read over the radio, as this one prepared by Aufschnaiter:

“We have the honour to announce that Radio Lhasa will broadcast an announcement of the enthronement of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, the ruler of Tibet, together with a proclamation of the Tibetan government to the Tibetan people and the world, on Friday 17 November 1950, at 5.45 p.m. Indian Standard Time.”

47 Statement by Westerners who visited Tibet before 1949 (London13 September 1994). Mr Robert Ford, Mrs Ronguy Collectt (daughter of Sir Charles Bell), Dr Bruno Beger, Mr Henreich Harrer, Mrs Joan Mary Jehu , Mr Archibald Jack, Prof. Fosco Maraini and Mr Kazi Sonam Togpyal of Sikkim. http://www.tibet.com/Status/statement.html

48David, MacDonald. Twenty Years in Tibet. New Delhi: Vintage Books, 1991. (first published 1932). pg 287.

49 Brauen, Martin. Peter Aufschnaiter’s Eight Years in Tibet. Bangkok: Orchid Press, 2002.

50 Harrer, Heinrich. Seven Years in Tibet. London: Rupert Hart Davis, 1953.

51 Richardson, H.E. High Peaks Pure Earth: Collected Writings on Tibetan History & Culture. London: Serindia Publications, 1998.

Richardson, H.E. Tibet and Its History. London: Oxford University Press, 1962.

Richardson, H.E. and David Snellgrove. A Cultural History of Tibet. London: George Wiedenfeld & Nicholson,1968.

52 Bell, Charles. Portrait of a Dalai Lama: The Life and Times of the Great Thirteenth. Boston: Wisdom Publications, 1987. pg 396.

53 Norbu, Jamyang. “Running-Dog Propagandists” Phayul.com, [Monday, July 14, 2008 09:37], http://www.phayul.com/news/article.aspx?id=21945&article=Running-Dog+Propagandists+-+Jamyang+Norbu&t=1&c=4

54 Shen, Tsung-lien and Shen-chi Liu. Tibet and the Tibetans. California: Stanford University Press, 1953. pg 112.

Compiled By JAMYANG NORBU for the Rangzen Alliance